In previous posts, we explored aspects of cultural astronomy in the Torres Strait. The indigenous people of these islands have a culture based on astronomy, yet the last major work on Islander astronomy was published in 1907. And even then the author clarified that his study was grossly incomplete. In the 1993 book "Stars of Tagai" by Nonie Sharp (Aboriginal Studies Press), she explained how Islander people were guided by Tagai - who is seen as a large constellation stretching from the Southern Cross to Corvus, down to Scorpius. Although the book contains important astronomical information, it is not about Islander astronomy and it does not shed light on Islander knowledge relating to the Milky Way, Magellanic Clouds, sun, moon, any of the planets, or other astronomical phenomena.

This left a gap in our knowledge about cultural astronomy in the Torres Strait. Dr Duane Hamacher, a Lecturer in the Nura Gili Indigenous Programs Unit at the University of New South Wales, realised the importance of this work and the fact that Islander staff at Nura Gili have close connections with their home country. In March 2013, he applied for a research grant through the Australian Research Council called the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA). This highly competitive grant is designed to support researchers who are in the early stages of their academic careers (within 5 years of being awarded a PhD).

Dr Hamacher was successful and was awarded a DECRA to study Islander astronomy. The grant, worth $350,000, will cover the project over a period of three years.

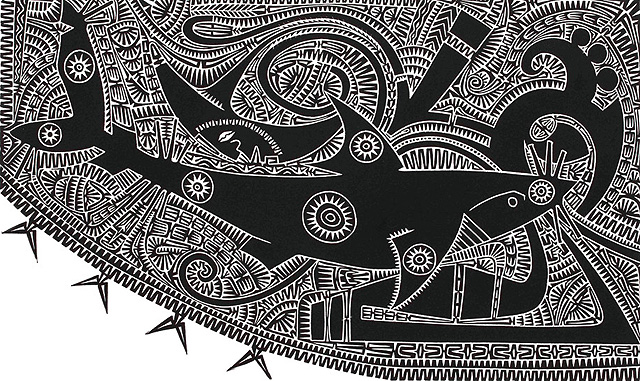

Project Description: The astronomical knowledge of Indigenous people across the world has gained much significance as scientists continue to unravel the embedded knowledge in material culture and oral traditions. As social scientists gain a stronger role in emerging scholarship on Indigenous astronomy, growing evidence of celestial knowledge is being rediscovered in artefacts, iconography, document archives, literature, folklore, music, language and performances. This project seeks to investigate an underexplored area of astronomical knowledge in Australia. It will be the first comprehensive study of the astronomical traditions of Torres Strait Islanders and will add to the growing body of knowledge regarding Indigenous astronomy.

This project will involve surveying over 1500 published documents on Islander culture, exploring archival documents in libraries, studying artefacts and artworks in museums across Australia and Europe, and conducting ethnographic fieldwork in the Torres Strait. This is where Dr Hamacher will live with Islander communities to learn firsthand from elders about their astronomical knowledge and practices. See the video below about current efforts to explore and record Islander astronomy in the Torres Strait.